PERIOD 2:1607–1754

Key Concept 2.1: Europeans developed a variety of colonization and migration patterns, influenced by different imperial goals, cultures, and the varied North American environments where they settled, and they competed with each other and American Indians for resources.

I. Spanish, French, Dutch, and British colonizers had different economic and imperial goals involving land and labor that shaped the social and political development of their colonies as well as their relationships with native populations.

A) Spanish efforts to extract wealth from the land led them to develop institutions based on subjugating native populations, converting them to Christianity, and incorporating them, along with enslaved and free Africans, into the Spanish colonial society.

B) French and Dutch colonial efforts involved relatively few Europeans and relied on trade alliances and intermarriage with American Indians to build economic and diplomatic relationships and acquire furs and other products for export to Europe.

C) English colonization efforts attracted a comparatively large number of male and female British migrants, as well as other European migrants, all of whom sought social mobility, economic prosperity, religious freedom, and improved living conditions. These colonists focused on agriculture and settled on land taken from Native Americans, from whom they lived separately.

Key Concept 2.1: Europeans developed a variety of colonization and migration patterns, influenced by different imperial goals, cultures, and the varied North American environments where they settled, and they competed with each other and American Indians for resources.

II. In the 17th century, early British colonies developed along the Atlantic coast, with regional differences that reflected various environmental, economic, cultural, and demographic factors.

A) The Chesapeake and North Carolina colonies grew prosperous exporting tobacco — a labor-intensive product initially cultivated by white, mostly male indentured servants and later by enslaved Africans.

B) The New England colonies, initially settled by Puritans, developed around small towns with family farms and achieved a thriving mixed economy of agriculture and commerce.

C) The middle colonies supported a flourishing export economy based on cereal crops and attracted a broad range of European migrants, leading to societies with greater cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity and tolerance.

D) The colonies of the southernmost Atlantic coast and the British West Indies used long growing seasons to develop plantation economies based on exporting staple crops. They depended on the labor of enslaved Africans, who often constituted the majority of the population in these areas and developed their own forms of cultural and religious autonomy.

E) Distance and Britain’s initially lax attention led to the colonies creating self-governing institutions that were unusually democratic for the era. The New England colonies based power in participatory town meetings, which in turn elected members to their colonial legislatures; in the Southern colonies, elite planters exercised local authority and also dominated the elected assemblies.

Key Concept 2.1: Europeans developed a variety of colonization and migration patterns, influenced by different imperial goals, cultures, and the varied North American environments where they settled, and they competed with each other and American Indians for resources.

III. Competition over resources between European rivals and American Indians encouraged industry and trade and led to conflict in the Americas.

III. Competition over resources between European rivals and American Indians encouraged industry and trade and led to conflict in the Americas.

A) An Atlantic economy developed in which goods, as well as enslaved Africans and American Indians, were exchanged between Europe, Africa, and the Americas through extensive trade networks. European colonial economies focused on acquiring, producing, and exporting commodities that were valued in Europe and gaining new sources of labor.

B) Continuing trade with Europeans increased the flow of goods in and out of American Indian communities, stimulating cultural and economic changes and spreading epidemic diseases that caused radical demographic shifts.

C) Interactions between European rivals and American Indian populations fostered both accommodation and conflict. French, Dutch, British, and Spanish colonies allied with and armed American Indian groups, who frequently sought alliances with Europeans against other Indian groups.

D) The goals and interests of European leaders and colonists at times diverged, leading to a growing mistrust on both sides of the Atlantic. Colonists, especially in British North America, expressed dissatisfaction over issues including territorial settlements, frontier defense, self-rule, and trade.

E) British conflicts with American Indians over land, resources, and political boundaries led to military confrontations, such as Metacom’s War (King Philip’s War) in New England.

F) American Indian resistance to Spanish colonizing efforts in North America, particularly after the Pueblo Revolt, led to Spanish accommodation of some aspects of American Indian culture in the Southwest.

Key Concept 2.2: The British colonies participated in political, social, cultural, and economic exchanges with Great Britain that encouraged both stronger bonds with Britain and resistance to Britain’s control.

I. Transatlantic commercial, religious, philosophical, and political exchanges led residents of the British colonies to evolve in their political and cultural attitudes as they became increasingly tied to Britain and one another.

A) The presence of different European religious and ethnic groups contributed to a significant degree of pluralism and intellectual exchange, which were later enhanced by the first Great Awakening and the spread of European Enlightenment ideas.

B) The British colonies experienced a gradual Anglicization over time, developing autonomous political communities based on English models with influence from intercolonial commercial ties, the emergence of a trans-Atlantic print culture, and the spread of Protestant evangelicalism.

C) The British government increasingly attempted to incorporate its North American colonies into a coherent, hierarchical, and imperial structure in order to pursue mercantilist economic aims, but conflicts with colonists and American Indians led to erratic enforcement of imperial policies.

D) Colonists’ resistance to imperial control drew on local experiences of self-government, evolving ideas of liberty, the political thought of the Enlightenment, greater religious independence and diversity, and an ideology critical of perceived corruption in the imperial system.

Key Concept 2.2: The British colonies participated in political, social, cultural, and economic exchanges with Great Britain that encouraged both stronger bonds with Britain and resistance to Britain’s control.

II. Like other European empires in the Americas that participated in the Atlantic slave trade, the English colonies developed a system of slavery that reflected the specific economic, demographic, and geographic characteristics of those colonies.

A) All the British colonies participated to varying degrees in the Atlantic slave trade due to the abundance of land and a growing European demand for colonial goods, as well as a shortage of indentured servants. Small New England farms used relatively few enslaved laborers, all port cities held significant minorities of enslaved people, and the emerging plantation systems of the Chesapeake and the southernmost Atlantic coast had large numbers of enslaved workers, while the great majority of enslaved Africans were sent to the West Indies.

B) As chattel slavery became the dominant labor system in many southern colonies, new laws created a strict racial system that prohibited interracial relationships and defined the descendants of African American mothers as black and enslaved in perpetuity.

C) Africans developed both overt and covert means to resist the dehumanizing aspects of slavery and maintain their family and gender systems, culture, and religion.

Study Questions for Jonathan Edwards – “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”

2. Edwards often defended the “preaching of terror” in order to frighten people away from hell and make them aware of the danger to their souls. How does he do this in “Sinners?” Which images strike you as the most vivid?

3. Some scholars have argued that Edwards’ preaching reflected the impact of life on the frontier. Do you see any signs of this in “Sinners”?

4. When you read Edwards’ sermon, how does it seem to differ from what you know about earlier Puritan/Calvinist preaching?

5. During the period of the Great Awakening, the term “harvest” was used to describe the “ingathering” of souls at church services. Why is this a useful term? Why would it have appealed to the people of Edwards’ day?

Mourt’s Relation

NOTE: Mourt’s Relation was an early Pilgrim booklet written mainly by Edward Winslow with significant contributions from William Bradford. Published in England (likely by George Morton), it provides a firsthand account of the early struggles of Pilgrims in exploring Cape Cod and then settling at Plymouth as well as early interactions with Native inhabitants. The excerpt here describes the first very brief encounter between Pilgrim settlers and Native Americans on November 15, 1620.

Wednesday, the 15th of November, they were set ashore, and when they had ordered themselves in the order of a single file and marched about the space of a mile, by the sea they espied five or six people with a dog, coming towards them, who were savages, who when they saw them, ran into the wood and whistled the dog after them, etc. First they supposed them to be Master Jones, the master, and some of his men, for they were ashore and knew of their coming, but after they knew them to be Indians they marched after them into the woods, lest other of the Indians should lie in ambush; but when the Indians saw our men following them, they ran away with might and main and our men turned out of the wood after them, for it was the way they intended to go, but they could not come near them. They followed them that night about ten miles by the trace of their footings, and saw how they had come the same way they went, and at a turning perceived how they ran up a hill, to see whether they followed them. At length night came upon them, and they were constrained to take up their lodging, so they set forth three sentinels, and the rest, some kindled a fire, and others fetched wood, and there held our rendezvous that night.

NOTE: The following excerpt describes the first extended encounter of Pilgrim settlers and Native Americans in March of 1621.

Friday, the 16th [of March], a fair warm day; towards this morning we determined to conclude of the military orders, which we had begun to consider of before but were interrupted by the savages, as we mentioned formerly. And whilst we were busied hereabout, we were interrupted again, for there presented himself a savage, which caused an alarm. He very boldly came all alone and along the houses straight to the rendezvous, where we intercepted him, not suffering him to go in, as undoubtedly he would, out of his boldness. He saluted us in English, and bade us welcome, for he had learned some broken English among the Englishmen that came to fish at Monchiggon, and knew by name the most of the captains, commanders, and masters that usually came. He was a man free in speech, so far as he could express his mind, and of a seemly carriage. We questioned him of many things; he was the first savage we could meet withal.….The wind being to rise a little, we cast a horseman's coat about him, for he was stark naked, only a leather about his waist, with a fringe about a span long, or little more; he had a bow and two arrows, the one headed, and the other unheaded. He was a tall straight man, the hair of his head black, long behind, only short before, none on his face at all; he asked some beer, but we gave him strong water and biscuit, and butter, and cheese, and pudding, and a piece of mallard, all which he liked well, and had been acquainted with such amongst the English. He told us the place where we now live is called Patuxet, and that about four years ago all the inhabitants died of an extraordinary plague, and there is neither man, woman, nor child remaining, as indeed we have found none, so as there is none to hinder our possession, or to lay claim unto it. …

Saturday and Sunday, reasonable fair days. On this day came again the savage, and brought with him five other tall proper men; they had every man a deer's skin on him, and the principal of them had a wild cat's skin, or such like on the one arm. They had most of them long hosen up to their groins, close made; and above their groins to their waist another leather, they were altogether like the Irish-trousers. They are of a complexion like our English gypsies, no hair or very little on their faces, on the heads long hair to their shoulders, only cut before, some trussed up before with a feather, broad-wise, like a fan, another a fox tail hanging out. These left (according to our charge given him before) their bows and arrows a quarter of a mile from our town. We gave them entertainment as we thought was fitting them; they did eat liberally of our English victuals. They made semblance unto us of friendship and amity; they sang and danced after their manner, like antics. They brought with them in a thing like a bow-case (which the principal of them had about his waist) a little of their corn pounded to powder, which, put to a little water, they eat. He had a little tobacco in a bag, but none of them drank but when he listed.

Edward Winslow, description of the first Thanksgiving

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after have a special manner to rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the company almost a week, at which time amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain, and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.

We have found the Indians very faithful in their covenant of peace with us; very loving and ready to pleasure us; we often go to them, and they come to us; some of us have been fifty miles by land in the country with them, the occasions and relations whereof you shall understand by our general and more full declaration of such things as are worth the noting, yea, it has pleased God so to possess the Indians with a fear of us, and love unto us, that not only the greatest king amongst them, called Massasoit, but also all the princes and peoples round about us, have either made suit unto us, or been glad of any occasion to make peace with us, so that seven of them at once have sent their messengers to us to that end. Yea, an Isle at sea, which we never saw, hath also, together with the former, yielded willingly to be under the protection, and subjects to our sovereign lord King James, so that there is now great peace amongst the Indians themselves, which was not formerly, neither would have been but for us; and we for our parts walk as peaceably and safely in the wood as in the highways in England. We entertain them familiarly in our houses, and they as friendly bestowing their venison on us. They are a people without any religion or knowledge of God, yet very trusty, quick of apprehension, ripe-witted, just.

William Bradford, treaty with Massasoit, Of Plymouth Plantation (excerpt), 1651

NOTE: The treaty with Massasoit was included in the record of activities in the Plymouth colony keep by William Bradford called Of Plymouth Plantation.

Their great Sachem[chief], called Massasoiet. who, about four or five days after, came with the chief of his friends and other attendance, with the aforesaid Squanto. With whom, after friendly entertainment and some gifts given him, they made a peace with him (which hath now continued this 24 years) in these terms:

I. That neither he nor any of his, should injure or do hurt to any of their people.

II. That if any of his did any hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender that they might punish him.

III. That if any thing were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his.

IV. That if any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; and if any did war against them, he should aid them.

V. That he should send to his neighbours confederates to certify them of this, that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

VI. That when their men came to them, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them.

William Bradford, description of an outbreak of smallpox among the Wampanoag, Of Plymouth Plantation (excerpt), 1651

NOTE: Disease for which they had no immunities tore through Native Americans communities soon after their first extended contact with Europeans. William Bradford describes one such outbreak in Of Plymouth Plantation, his record of activities written over a three decades from 1621 to 1651

This spring, also, those Indians that lived about their trading house there fell sick of the smallpox, and died most miserably; for a sorer disease cannot befall them; they fear it more than the plague, for usually they that have this disease have them in abundance, and for want of bedding and linen and other helps, they fall into a lamentable condition, as they lie on their hard mats, the pox breaking and mattering, and running one into another, their skin cleaving (by reason thereof) to the mats they lie on; when they turn them a whole side will flay off at once, (as it were) and they will be all of a gore blood, most fearful to behold; and then being very sore, what with cold and other distempers, they die like rotten sheep. The condition of this people was so lamentable, and they fell down so generally of this disease, as they were (in the end) not able to help one another; no, not to make a fire, nor to fetch a little water to drink, nor any to bury the dead; but would strive as long as they could, and when they could procure no other means to make fire, they would burn the wooden trays and dishes they ate their meat in, and their very bows and arrows, and some would crawl out on all fours to get a little water, and sometimes die by the way, and not be able to get in again. But those of the English house (though at first they were afraid of the infection) yet seeing their woeful and sad condition, and hearing their pitiful cries and lamentations, they had compassion of them, and daily fetched them wood and water, and made them fires, got them victuals whilst they lived, and buried them when they died. For very few of them escaped, notwithstanding they did what they could for them, to the hazzard of themselves. The chief Sachem himself now died, and almost all his friends and kindred. But by the marvelous goodness and providence of God not one of the English was so much as sick, or in the least measure tainted with this disease though they daily did these offices for them for many weeks together. And this mercy which they showed them was kindly taken, and thankfully acknowledged of all the Indians that knew or heard of the same; and their ministers here did much commend and reward them for the same….

In the winter in the year 1674 an Indian was found dead, and by a Coroner’s inquest of Plymouth Colony judged murdered. He was found dead in a hole through ice broken in a pond, with his gun and some fowl by him. Some English supposed him thrown in. Some Indians that I judged intelligible and impartial in that case did think he fell in, and was so drowned and that the ice did hurt his throat, as the English said it was cut; but they acknowledged that sometimes naughty Indians would kill others but not, as ever they heard, to obscure it, as if the dead Indian was not murdered.…And the report came, that the three Indians had confessed and accused Philip so to employ them, and that the English would hang Philip, so the Indians were afraid, and reported that the English had flattered them (or by threats) to belie Philip that they might kill him to have his Land; and that if Philip had done it, it was their Law so to execute whomever their kings judged deserved it, and that he had no cause to hide it. …

Then to endeavor to prevent [war], we sent a man to Philip to say that if he would come to the ferry, we would come over to speak with him,…Philip called his council and agreed to come to us; he came himself unarmed and about 40 of his men armed.…The Indians owned that fighting was the worst way; then they propounded how right might take place…. They said they had been the first in doing good to the English, and the English the first in doing wrong; they said when the English first came, their king’s father was as a great man and the English as a little child. He constrained other Indians from wronging the English and gave them corn and showed them how to plant and was free to do them any good and had let them have a 100 times more land than now the king had for his own people. But [Metacom’s] brother, when he was king, came miserably to die by being forced into court and, as they judged, poisoned. And another grievance was if 20 of their honest Indians testified that a Englishman had done them wrong, it was as nothing; and if but one of their worst Indians testified against any Indian or their king when it pleased the English, that was sufficient. Another grievance was when their kings sold land the English would say it was more than they agreed to and a writing must be proof against all them, and some of their kings had done wrong to sell so much that he left his people none, and some being given to drunkenness, the English made them drunk and then cheated them in bargains, but now their kings were forewarned not to part with land for nothing in comparison to the value thereof.…Another grievance was that the English cattle and horses still increased so that when they removed 30 miles from where the English had anything to do, they could not keep their corn from being spoiled, they never being used to fence, and thought that when the English bought land of them that they would have kept their cattle upon their own land. Another grievance was that the English were so eager to sell the Indians liquors that most of the Indians spent all in drunkenness and then ravened upon the sober Indians and, they did believe, often did hurt the English cattle, and their kings could not prevent it.…In this time some Indians fell to pilfering some houses that the English had left, and an old man and a lad going to one of those houses did see 3 Indians run out thereof. The old man bid the young man shoot, so he did, and an Indian fell down but got away again. It is reported that then some Indians came to the garrison and asked why they shot the Indian. They asked whether he was dead. The Indians said yea. An English lad said it was no matter. The men endeavored to inform them it was but an idle lad’s words, but the Indians in haste went away and did not harken to them. The next day the lad that shot the Indian and his father and five more English were killed; so the war began with Philip.…But I am confident it would be best for English and Indians that a peace were made upon honest terms for each to have a due propriety and to enjoy it without oppression or usurpation by one to the other. But the English dare not trust the Indians’ promises; neither the Indians to the English’s promises; and each has great cause therefore.

NOTE: The treaty with Massasoit was included in the record of activities in the Plymouth colony keep by William Bradford called Of Plymouth Plantation.

Their great Sachem[chief], called Massasoiet. who, about four or five days after, came with the chief of his friends and other attendance, with the aforesaid Squanto. With whom, after friendly entertainment and some gifts given him, they made a peace with him (which hath now continued this 24 years) in these terms:

I. That neither he nor any of his, should injure or do hurt to any of their people.

II. That if any of his did any hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender that they might punish him.

III. That if any thing were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his.

IV. That if any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; and if any did war against them, he should aid them.

V. That he should send to his neighbours confederates to certify them of this, that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

VI. That when their men came to them, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them.

William Bradford, description of an outbreak of smallpox among the Wampanoag, Of Plymouth Plantation (excerpt), 1651

NOTE: Disease for which they had no immunities tore through Native Americans communities soon after their first extended contact with Europeans. William Bradford describes one such outbreak in Of Plymouth Plantation, his record of activities written over a three decades from 1621 to 1651

This spring, also, those Indians that lived about their trading house there fell sick of the smallpox, and died most miserably; for a sorer disease cannot befall them; they fear it more than the plague, for usually they that have this disease have them in abundance, and for want of bedding and linen and other helps, they fall into a lamentable condition, as they lie on their hard mats, the pox breaking and mattering, and running one into another, their skin cleaving (by reason thereof) to the mats they lie on; when they turn them a whole side will flay off at once, (as it were) and they will be all of a gore blood, most fearful to behold; and then being very sore, what with cold and other distempers, they die like rotten sheep. The condition of this people was so lamentable, and they fell down so generally of this disease, as they were (in the end) not able to help one another; no, not to make a fire, nor to fetch a little water to drink, nor any to bury the dead; but would strive as long as they could, and when they could procure no other means to make fire, they would burn the wooden trays and dishes they ate their meat in, and their very bows and arrows, and some would crawl out on all fours to get a little water, and sometimes die by the way, and not be able to get in again. But those of the English house (though at first they were afraid of the infection) yet seeing their woeful and sad condition, and hearing their pitiful cries and lamentations, they had compassion of them, and daily fetched them wood and water, and made them fires, got them victuals whilst they lived, and buried them when they died. For very few of them escaped, notwithstanding they did what they could for them, to the hazzard of themselves. The chief Sachem himself now died, and almost all his friends and kindred. But by the marvelous goodness and providence of God not one of the English was so much as sick, or in the least measure tainted with this disease though they daily did these offices for them for many weeks together. And this mercy which they showed them was kindly taken, and thankfully acknowledged of all the Indians that knew or heard of the same; and their ministers here did much commend and reward them for the same….

John Easton, an account of Metacom describing Native American complaints about the English Settlers, A Relation of the Indian War (excerpts), 1675

NOTE: Metacom, also known as King Philip, leader of the Wampanoag near Plymouth colony, led many other Native Americans into a widespread revolt against the colonists of southern New England in 1675. The conflict had been brewing for some time over a set of longstanding grievances between Europeans and Native Americans. In that tense atmosphere, John Easton, attorney general of the Rhode Island colony, met King Philip in June 1675 in an effort to negotiate a settlement. Easton recorded King Philip’s complaints, including the steady loss of Wampanoag land to the Europeans, the English colonists’ growing herds of cattle and their destruction of Native American crops, and the unequal justice Native Americans received in the English courts. This meeting between Easton and Metacom proved futile, however, and the war (which became the bloodiest in US history relative to the size of the population) began late that month.In the winter in the year 1674 an Indian was found dead, and by a Coroner’s inquest of Plymouth Colony judged murdered. He was found dead in a hole through ice broken in a pond, with his gun and some fowl by him. Some English supposed him thrown in. Some Indians that I judged intelligible and impartial in that case did think he fell in, and was so drowned and that the ice did hurt his throat, as the English said it was cut; but they acknowledged that sometimes naughty Indians would kill others but not, as ever they heard, to obscure it, as if the dead Indian was not murdered.…And the report came, that the three Indians had confessed and accused Philip so to employ them, and that the English would hang Philip, so the Indians were afraid, and reported that the English had flattered them (or by threats) to belie Philip that they might kill him to have his Land; and that if Philip had done it, it was their Law so to execute whomever their kings judged deserved it, and that he had no cause to hide it. …

Then to endeavor to prevent [war], we sent a man to Philip to say that if he would come to the ferry, we would come over to speak with him,…Philip called his council and agreed to come to us; he came himself unarmed and about 40 of his men armed.…The Indians owned that fighting was the worst way; then they propounded how right might take place…. They said they had been the first in doing good to the English, and the English the first in doing wrong; they said when the English first came, their king’s father was as a great man and the English as a little child. He constrained other Indians from wronging the English and gave them corn and showed them how to plant and was free to do them any good and had let them have a 100 times more land than now the king had for his own people. But [Metacom’s] brother, when he was king, came miserably to die by being forced into court and, as they judged, poisoned. And another grievance was if 20 of their honest Indians testified that a Englishman had done them wrong, it was as nothing; and if but one of their worst Indians testified against any Indian or their king when it pleased the English, that was sufficient. Another grievance was when their kings sold land the English would say it was more than they agreed to and a writing must be proof against all them, and some of their kings had done wrong to sell so much that he left his people none, and some being given to drunkenness, the English made them drunk and then cheated them in bargains, but now their kings were forewarned not to part with land for nothing in comparison to the value thereof.…Another grievance was that the English cattle and horses still increased so that when they removed 30 miles from where the English had anything to do, they could not keep their corn from being spoiled, they never being used to fence, and thought that when the English bought land of them that they would have kept their cattle upon their own land. Another grievance was that the English were so eager to sell the Indians liquors that most of the Indians spent all in drunkenness and then ravened upon the sober Indians and, they did believe, often did hurt the English cattle, and their kings could not prevent it.…In this time some Indians fell to pilfering some houses that the English had left, and an old man and a lad going to one of those houses did see 3 Indians run out thereof. The old man bid the young man shoot, so he did, and an Indian fell down but got away again. It is reported that then some Indians came to the garrison and asked why they shot the Indian. They asked whether he was dead. The Indians said yea. An English lad said it was no matter. The men endeavored to inform them it was but an idle lad’s words, but the Indians in haste went away and did not harken to them. The next day the lad that shot the Indian and his father and five more English were killed; so the war began with Philip.…But I am confident it would be best for English and Indians that a peace were made upon honest terms for each to have a due propriety and to enjoy it without oppression or usurpation by one to the other. But the English dare not trust the Indians’ promises; neither the Indians to the English’s promises; and each has great cause therefore.

MASSACHUSETTS

Governor John Winthrop: A Model of Christian Charity (1630 on board the Arbella) Excerpt

Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others’ necessities. We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality. We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body. So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace. The Lord will be our God, and delight to dwell among us, as His own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways, so that we shall see much more of His wisdom, power, goodness and truth, than formerly we have been acquainted with. We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when He shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations, "may the Lord make it like that of New England." For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. We shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God, and all professors for God's sake. We shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.

And to shut this discourse with that exhortation of Moses, that faithful servant of the Lord, in his last farewell to Israel, Deut. 30. "Beloved, there is now set before us life and death, good and evil," in that we are commanded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another, to walk in his ways and to keep his Commandments and his ordinance and his laws, and the articles of our Covenant with Him, that we may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God may bless us in the land whither we go to possess it. But if our hearts shall turn away, so that we will not obey, but shall be seduced, and worship other Gods, our pleasure and profits, and serve them; it is propounded unto us this day, we shall surely perish out of the good land whither we pass over this vast sea to possess it.

Therefore let us choose life,

that we and our seed may live,

by obeying His voice and cleaving to Him,

for He is our life and our prosperity.

Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others’ necessities. We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality. We must delight in each other; make others’ conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body. So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace. The Lord will be our God, and delight to dwell among us, as His own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways, so that we shall see much more of His wisdom, power, goodness and truth, than formerly we have been acquainted with. We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when He shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding plantations, "may the Lord make it like that of New England." For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. We shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God, and all professors for God's sake. We shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.

And to shut this discourse with that exhortation of Moses, that faithful servant of the Lord, in his last farewell to Israel, Deut. 30. "Beloved, there is now set before us life and death, good and evil," in that we are commanded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another, to walk in his ways and to keep his Commandments and his ordinance and his laws, and the articles of our Covenant with Him, that we may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God may bless us in the land whither we go to possess it. But if our hearts shall turn away, so that we will not obey, but shall be seduced, and worship other Gods, our pleasure and profits, and serve them; it is propounded unto us this day, we shall surely perish out of the good land whither we pass over this vast sea to possess it.

Therefore let us choose life,

that we and our seed may live,

by obeying His voice and cleaving to Him,

for He is our life and our prosperity.

William Bradford Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647.

Religious Beliefs

The one side [the Reformers] labored to have ye right worship of God & discipline of Christ established in ye church, according to ye simplicity of ye gospel, without the mixture of men inventions, and to have & to be ruled by ye laws of Gods word, dispensed in those offices, & by those officers of Pastors, Teachers, & Elders, &c. according to ye Scriptures.

The other party [the Church of England], though under many colors & pretenses, endeavored to have ye episcopal dignities (affter ye popish manner) with their large power & jurisdiction still retained; with all those courts, cannons, & ceremonies, together with all such livings, revenues, & subordinate officers, with other such means as formerly upheld their anti christian greatness, and enabled them with lordly & tyrannous power to persecute ye poor servants of God.

Questions for Religious Beliefs

1. What did the Reformers believe in?

2. What do the Pilgrims (Reformers) see as the problem with the Church of England?

1. What did the Reformers believe in?

2. What do the Pilgrims (Reformers) see as the problem with the Church of England?

Moving to the City of Leiden, Holland (1609)

For these & some other reasons they removed to Leyden, a fair & bewtifull citie, and of a sweete situation, but made more famous by ye universitie wherwith it is adorned, in which of late had been so many learned man. But wanting that traffike by sea which Amerstdam injoyes, it was not so beneficiall for their outward means of living & estats. But being now hear pitchet they fell to such trads & imployments as they best could; valewing peace & their spirituall comforte above any other riches whatsoever. And at lenght they came to raise a competente & comforteable living, but with hard and continuall labor.

Being thus settled (after many difficulties) they continued many years in a comfortable condition, injoying much sweete & delightefull societies & spirituall comforte togeather in ye wayes of God, under ye able ministrie, and prudente governmente of Mr. John Robinson, & Mr. William Brewster, who was an assistante unto him in ye place of an Elder, unto which he was now called & chosen by the church.

So as they grew in knowledge & other gifts & graces of ye spirite of God, & lived togeather in peace, & love, and holiness; and many came unto them from diverse parts of England, so as they grew a great congregation. And if at any time any differences arose, or offences broak out (as it cannot be, but some time ther will, even amongst ye best of men) they were ever so mete with, and nipt in ye head betims, or otherwise so well composed, as still love, peace, and communion was continued; or else ye church purged ot those that were incurable & incorrigible, when, after much patience used, no other means would serve, which seldom came to pass.

Questions for Moving to the City of Leiden, Holland (1609)

3. What was life like for the Pilgrims after they moved to Leiden?

3. What was life like for the Pilgrims after they moved to Leiden?

Deciding to Emigrate to America

All great & honourable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and must be both enterprised and overcome with answerable courages. It was granted ye dangers were great, but not desperate; the difficulties were many, but not invincible. For though there were many of them likely, yet they were not cartaine; it might be sundrie of ye things feared might never befale; others by providente care & ye use of good means, might in a great measure be prevented; and all of them, through ye help of God, by fortitude and patience, might either be borne, or overcome.

True it was, that such atempts were not to be made and undertaken without good ground & reason; not rashly or lightly as many have done for curiositie or hope of gaine, &c. But their condition was not ordinarie; their ends were good & honourable; their calling lawfull, & urgente; and therfore they might expecte ye blessing of god in their proceding. Yea, though they should loose their lives in this action, yet might they have comforte in the same, and their endeavors would be honourable. They lived hear but as men in exile, & in a poore condition; and as great miseries might possibly befale them in this place, for ye 12. years of truce [the truce between Holland and Spain] were now out, & ther was nothing but beating of drumes, and preparing for warr, the events wherof are allway uncertaine.

Questions for Deciding to Emigrate to America

4. Why did the Pilgrims decide to move to America in spite of the dangers?

4. Why did the Pilgrims decide to move to America in spite of the dangers?

Arriving Safely at Cape Cod

Being thus arived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees & blessed ye God of heaven, who had brought them over ye vast & furious ocean, and delivered them from all ye periles & miseries therof, againe to set their feete on ye firme and stable earth, their proper elemente. And no marvell if they were thus joyefull, seeing wise Seneca was so affected with sailing a few miles on ye coast of his owne Italy; as he affirmed, that he had rather remaine twentie years on his way by land, then pass by sea to any place in a short time; so tedious & dreadfull was ye same unto him.

But hear I cannot but stay and make a pause, and stand half amased at this poore peoples presente condition; and so I thinke will the reader too, when he well considered ye same. Being thus passed ye vast ocean, and a sea of troubles before in their preparation (as may be remembred by yt which wente before), they had now no friends to wellcome them, nor inns to entertaine or refresh their weather beaten bodys, no houses or much less townes to repaire too, to seeke for succoure.

Let it also be considred what weake hopes of supply & succoure they left behinde them, yt might bear up their minds in this sade condition and trialls they were under; and they could not but be very smale. It is true, indeed, ye affections & love of their brethren at Leyden was cordiall & entire towards them, but they had litle power to help them, or them selves; and how ye case stode betweene them & ye marchants at their coming away, hath already been declared. What could not sustaine them but ye spirite of God & his grace? May not & ought not the children of these fathers rightly say : Our faithers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this willdernes; but they cried unto ye Lord, and he heard their voyce, and looked on their adversitie…

Questions for Arriving Safely at Cape Cod

5. What attitude did the Pilgrims have toward their arrival in Cape Cod?

5. What attitude did the Pilgrims have toward their arrival in Cape Cod?

The Pilgrims’ Exploring Party Lands at Plymouth

From hence they departed, & co[a]sted all along, but discerned no place likely for harbor; & therfore hasted to a place that their pillote, (one Mr. Coppin who had bine in ye cuntrie before) did assure them was a good harbor, which he had been in, and they might fetch it before night; of which they were glad, for it begane to be foule weather.

After some houres sailing, it begane to snow & raine, & about ye midle of ye afternoone, ye wind increased, & ye sea became very rough, and they broake their ruder, & it was as much as 2 men could doe to steere her with a cupple of oares. But their pillott bad them be of good cheere, for he saw ye harbor; but ye storme increasing, & night drawing on, they bore what saile they could to gett in, while they could see. But herwith they broake their mast in 3 peeces, & their saill fell over bord, in a very grown sea, so as they had like to have been cast away; yet by Gods mercie they recovered them selves, & having ye floud with them, struck into ye harbore.

But when it came too, ye pillott was deceived in ye place, and said, ye Lord be mercifull unto them, for his eys never saw yt place before; & he & the mr. mate would have rune her ashore, in a cove full of breakers, before ye winde. But a lusty seaman which steered, bad those which rowed, if they were men, about with her, or ells they were all cast away; the which they did with speed. So he bid them be of good cheere & row lustly, for ther was a faire sound before them, & he doubted not but they should find one place or other wher they might ride in saftie. And though it was very darke, and rained sore, yet in ye end they gott under ye lee of a smale iland, and remained ther all yt night in saftie. But they knew not this to be an iland till morning, but were devided in their minds; some would keepe ye boate for fear they might be amongst ye Indians; others were so weake and cold, they could not endure, but got a shore, & with much adoe got fire, (all things being so wett,) and ye rest were glad to come to them; for after midnight ye wind shifted to the north-west, & it frose hard.

But though this had been a day & night of much trouble & danger unto them, yet God gave them a morning of comforte & refreshing (as usually he doth to his children), for ye next day was a faire sunshinig day, and they found them sellvs to be on an iland secure from ye Indeans, wher they might drie their stufe, fixe their peeces, & rest them selves, and gave God thanks for his mercies, in their manifould deliverances. And this being the last day of ye weeke, they prepared there to keepe ye Sabath.

On Munday they sounded ye harbor, and founde it fitt for shipping; and marched into ye land [Plymouth], & found diverse cornfeilds, & litle runing brooks, a place (as they supposed) fitt for situation; at least it was ye best they could find, and ye season, & their presente necessitie, made them glad to accepte of it. So they returned to their shipp againe with this news to ye rest of their people, which did much comforte their harts.

Questions for The Pilgrims’ Exploring Party Lands at Plymouth

6. To what do the Pilgrims attribute their safety and survival?

7. What happened to the Pilgrims’ exploring party before they arrived in Plymouth?

8. How did the Pilgrims react to hearing about Plymouth?

6. To what do the Pilgrims attribute their safety and survival?

7. What happened to the Pilgrims’ exploring party before they arrived in Plymouth?

8. How did the Pilgrims react to hearing about Plymouth?

Meeting Squanto, the Native American Who Spoke English

All this while the Indians came skulking about them, and would sometimes show themselves aloof off, but when any approached near them, they would run away; and once they stole away their tools where they had been at work and were gone to dinner.

But about the 16th of March, a certain Indian came boldly amongst them and spoke to them in broken English, which they could well understand but marveled at it. At length they understood by discourse with him, that he was not of these parts, but belonged to the eastern parts where some English ships came to fish, with whom he was acquainted and could name sundry of them by their names, amongst whom he had got his language. He became profitable to them in acquainting them with many things concerning the state of the country in the east parts where he lived, which was afterwards profitable unto them; as also of the people here, of their names, number and strength, of their situation and distance from this place, and who was chief amongst them. His name was Samoset. He told them also of another Indian whose name was Sguanto, a native of this place, who had been in England and could speak better English than himself.

Being after some time of entertainment and gifts dismissed, a while after he came again, and five more with him, and they brought again all the tools that were stolen away before, and made way for the coming of their great Sachem, called Massasoit. Who, about four or five days after, came with the chief of his friends and other attendance, with the aforesaid Squanto. With whom, after friendly entertainment and some gifts given him, they made a peace with him (which hath now continued this 24 years) in these terms:

1. That neither he nor any of his should injure or do hurt to any of their people.

2. That if any of his did hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender, that they might punish him.

3. That if anything were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his.

4. If any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; if any did war against them, he should aid them.

5. He should send to his neighbors confederates to certify them of this, that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

6. That when their men came to them, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them.

After these things he returned to his place called Sowams, some 40 miles from this place, but Squanto continued with them and was their interpreter and was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died.

He was a native of this place, and scarce any left alive besides himself. He we carried away with divers others by one Hunt, a master of a ship, who thought to sell them for slaves in Spain. But he got away for England and was entertained by a merchant in London, and employed to Newfoundland and other parts, and lastly brought hither into these parts by one Mr. Dermer, a gentleman employed by Sir Ferdinando Gorges and others for discovery and other designs in these parts.

Questions for Meeting Squanto, the Native American Who Spoke English

9. What did the agreement between Squanto and the Pilgrims state?

10. Why did the Pilgrims owe Squanto gratitude?

9. What did the agreement between Squanto and the Pilgrims state?

10. Why did the Pilgrims owe Squanto gratitude?

The Winter of 1621

In these hard & difficulte beginings they found some discontents & murmurings arise amongst some, and mutinous speeches & carriags in other; but they were soone quelled & overcome by ye wisdome, patience, and just & equall carrage of things by ye Govr and better part, wch clave faithfully togeather in ye maine. But that which was most sadd & lamentable was, that in 2. or 3. moneths time halfe of their company dyed, espetialy in Jan: & February, being ye depth of winter, and wanting houses & other comforts; being infected with ye scurvie & other diseases, which this long vioage & their inacomodate condition had brought upon them; so as ther dyed some times 2. or 3. of a day, in ye foresaid time; that of 100. & odd persons, scarce 50. remained.

And of these in ye time of most distres, ther was but 6. or 7. sound persons, who, to their great comendations be it spoken, spared no pains, night nor day, but with abundance of toyle and hazard of their owne health, fetched them woode, made them fires, drest them meat, made their beads, washed their lothsome cloaths, cloathed & uncloathed them; in a word, did all ye homly & necessarie offices for them wch dainty & quesie stomacks cannot endure to hear named; and all this willingly & cherfully, without any grudging in ye least, shewing herein their true love unto their friends & bretheren. A rare example & worthy to be remembred. Two of these 7. were Mr. William Brewster, ther reverend Elder, & Myles Standish, ther Captein & military comander, unto whom my selfe, & many others, were much beholden in our low & sicke condition.

Questions for The Winter of 1621

11. Why did so many people die during this winter?

11. Why did so many people die during this winter?

The First Thanksgiving Feast

They begane now to gather in ye small harvest they had, and to fitte up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health & strenght, and had all things in good plenty; fFor as some were thus imployed in affairs abroad, others were excersised in fishing, aboute codd, & bass, & other fish, of which yey tooke good store, of which every family had their portion. All ye somer ther was no want. And now begane to come in store of foule, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besids water foule, ther was great store of wild Turkies, of which they tooke many, besids venison, &c. Besids, they had about a peck a meale a weeke to a person, or now since harvest, Indean corn to yt proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largly of their plenty hear to their freinds in England, which were not fained, but true reports.

Questions for The First Thanksgiving Feast

12. The Pilgrims have been in Plymouth for almost a year. Which line from this excerpt signifies this?

13. What was the result of the harvest and the Thanksgiving feast?

12. The Pilgrims have been in Plymouth for almost a year. Which line from this excerpt signifies this?

13. What was the result of the harvest and the Thanksgiving feast?

Overall Question for William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation

Why might Bradford have written this in third person point of view instead of first person narrative?

VIRGINIA

Elizabeth I of England (1588)

- What does the document tell us?

- What inferences can be drawn from the document?

- What essential outside information can be teased from the document and used in a quality analysis?

Letter sent to the Virginia Company from Captain Smith (1608)

The Copy of a Letter sent to the Treasurer and Councell of Virginia from Captaine Smith, then President in Virginia. Right Honorable, etc.

I Received your Letter, wherein you write, that our minds are so set upon faction, and idle conceits in dividing the Country without your consents, and that we feed You but with ifs & ands, hopes, & some few proofes; as if we would keepe the mystery of the businesse to our selves: and that we must expresly follow your instructions sent by Captain Newport: the charge of whose voyage amounts to neare two thousand pounds, the which if we cannot defray by the Ships returne, we are like to remain as banished men. To these particulars I humbly intreat your Pardons if I offend you with my rude Answer.

For our factions, unlesse you would have me run away and leave the Country, I cannot prevent them: because I do make many stay that would els fly any whether. For the idle Letter sent to my Lord of Salisbury, by the President and his confederats, for dividing the Country &c. What it was I know not, for you saw no hand of mine to it; nor ever dream't I of any such matter. That we feed you with hopes, &c. Though I be no scholer, I am past a schoole-boy; and I desire but to know, what either you, and these here doe know, but that I have learned to tell you by the continuall hazard of my life. I have not concealed from you any thing I know; but I feare some cause you to beleeve much more then is true. Expresly to follow your directions by Captaine Newport, though they be performed, I was directly against it; but according to our Commission, I was content to be overruled by the major part of the Councell, I feare to the hazard of us all; which now is generally confessed when it is too late. Onely Captaine Winne and Captaine Waldo I have sworne of the Councell, and Crowned Powhatan according to your instructions.

For the charge of this Voyage of two or three thousand pounds, we have not received the value of an hundred pounds. And for the quartred Boat to be borne by the Souldiers over the Falles, Newport had 120 of the best men he could chuse. If he had burnt her to ashes, one might have carried her in a bag, but as she is, five hundred cannot, to a navigable place above the Falles. And for him at that time to find in the South Sea, a Mine of gold; or any of them sent by Sir Walter Raleigh: at our Consultation I told them was as likely as the rest. But during, this great discovery of thirtie myles, (which might as well have beene done by one man, and much more, for the value of a pound of Copper at a seasonable tyme) they had the Pinnace and all the Boats with them, but one that remained with me to serve the Fort. In their absence I followed the new begun workes of Pitch and Tarre, Glasse, Sopeashes, and Clapboord, whereof some small quantities we have sent you. But if you rightly consider, what an infinite toyle it is in Russia and Swethland, where the woods are proper for naught els, and though there be the helpe both of man and beast in those ancient Commonwealths, which many an hundred yeares have used it, yet thousands of those poore people can scarce get necessaries to live, but from hand to mouth. And though your Factors there can buy as much in a week as will fraught you a ship, or as much as you please; you must not expect from us any such matter, which are but a many of ignorant miserable soules, that are scarce able to get wherewith to live, and defend our selves against the inconstant Salvages: finding but here and there a tree fit for the purpose, and want all things els the Russians have.

For the Coronation of Powhatan, by whose advice you sent him such presents, I know not; but this give me leave to tell you, I feare they will be the confusion of us all ere we heare from you againe. At your Ships arrivall, the Salvages harvest was newly gathered, and we going to buy it, our owne not being halfe sufficient for so great a number. As for the two ships loading of Corne Newport promised to provide us from Powhatan, he brought us but foureteene Bushels; and from the Monacans nothing, but the most of the men sicke and neare famished. From your Ship we had not provision in victuals worth twenty pound, and we are more then two hundred to live upon this: the one halfe sicke, the other little better. For the Saylers (I confesse) they daily make good cheare, but our dyet is a little meale and water, and not sufficient of that. Though there be fish in the Sea, foules in the ayre, and Beasts in the woods, their bounds are so large, they so wilde, and we so weake and ignorant, we cannot much trouble them. Captaine Newport we much suspect to be the Authour of those inventions. Now that you should know, I have made you as great a discovery as he, for lesse charge then he spendeth you every meale; I have sent you this Mappe of the Bay and Rivers, with an annexed Relation of the Countries and Nations that inhabit them, as you may see at large. Also two barrels of stones, and such as I take to be good Iron ore at the least; so devided, as by their notes you may see in what places I found them. The Souldiers say many of your officers maintaine their families out of that you send us: and that Newport hath an hundred pounds a yeare for carrying newes.

For every master you have yet sent can find the way as well as he, so that an hundred pounds might be spared, which is more then we have all, that helpe to pay him wages. Cap. Ratliffe is now called Sicklemore, a poore counterfeited imposture. I have sent you him home, least the company should cut his throat. What he is, now every one can tell you: if he and Archer returne againe, they are sufficient to keepe us alwayes in factions. When you send againe I intreat you rather send but thirty Carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, fisher men, blacksmiths, masons, and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided; then a thousand of such as we have: for except wee be able both to lodge them, and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for any thing. Thus if you please to consider this account, and of the unnecessary wages to Captaine Newport, or his ships so long lingering and staying here (for notwithstanding his boasting to leave us victuals for 12 moneths, though we had 89 by this discovery lame and sicke, and but a pinte of Corne a day for a man, we were constrained to give him three hogsheads of that to victuall him homeward) or yet to send into Germany or Poleland for glasse-men & the rest, till we be able to sustaine our selves, and relieve them when they come. It were better to give five hundred pound a tun for those grosse Commodities in Denmarke, then send for them hither, till more necessary things be provided.

For in over-toyling our weake and unskilfull bodies, to satisfie this desire of present profit, we can scarce ever recover our selves from ore Supply to another. And I humbly intreat you hereafter, let us know what we should receive, and not stand to the Saylers courtesie to leave us what they please, els you may charge us with what you will, but we not you with any thing. These are the causes that have kept us in Virginia, from laying such a foundation, that ere this might have given much better content and satisfaction; but as yet you must not looke for any profitable returnes: so I humbly rest.

For our factions, unlesse you would have me run away and leave the Country, I cannot prevent them: because I do make many stay that would els fly any whether. For the idle Letter sent to my Lord of Salisbury, by the President and his confederats, for dividing the Country &c. What it was I know not, for you saw no hand of mine to it; nor ever dream't I of any such matter. That we feed you with hopes, &c. Though I be no scholer, I am past a schoole-boy; and I desire but to know, what either you, and these here doe know, but that I have learned to tell you by the continuall hazard of my life. I have not concealed from you any thing I know; but I feare some cause you to beleeve much more then is true. Expresly to follow your directions by Captaine Newport, though they be performed, I was directly against it; but according to our Commission, I was content to be overruled by the major part of the Councell, I feare to the hazard of us all; which now is generally confessed when it is too late. Onely Captaine Winne and Captaine Waldo I have sworne of the Councell, and Crowned Powhatan according to your instructions.

For the charge of this Voyage of two or three thousand pounds, we have not received the value of an hundred pounds. And for the quartred Boat to be borne by the Souldiers over the Falles, Newport had 120 of the best men he could chuse. If he had burnt her to ashes, one might have carried her in a bag, but as she is, five hundred cannot, to a navigable place above the Falles. And for him at that time to find in the South Sea, a Mine of gold; or any of them sent by Sir Walter Raleigh: at our Consultation I told them was as likely as the rest. But during, this great discovery of thirtie myles, (which might as well have beene done by one man, and much more, for the value of a pound of Copper at a seasonable tyme) they had the Pinnace and all the Boats with them, but one that remained with me to serve the Fort. In their absence I followed the new begun workes of Pitch and Tarre, Glasse, Sopeashes, and Clapboord, whereof some small quantities we have sent you. But if you rightly consider, what an infinite toyle it is in Russia and Swethland, where the woods are proper for naught els, and though there be the helpe both of man and beast in those ancient Commonwealths, which many an hundred yeares have used it, yet thousands of those poore people can scarce get necessaries to live, but from hand to mouth. And though your Factors there can buy as much in a week as will fraught you a ship, or as much as you please; you must not expect from us any such matter, which are but a many of ignorant miserable soules, that are scarce able to get wherewith to live, and defend our selves against the inconstant Salvages: finding but here and there a tree fit for the purpose, and want all things els the Russians have.

For the Coronation of Powhatan, by whose advice you sent him such presents, I know not; but this give me leave to tell you, I feare they will be the confusion of us all ere we heare from you againe. At your Ships arrivall, the Salvages harvest was newly gathered, and we going to buy it, our owne not being halfe sufficient for so great a number. As for the two ships loading of Corne Newport promised to provide us from Powhatan, he brought us but foureteene Bushels; and from the Monacans nothing, but the most of the men sicke and neare famished. From your Ship we had not provision in victuals worth twenty pound, and we are more then two hundred to live upon this: the one halfe sicke, the other little better. For the Saylers (I confesse) they daily make good cheare, but our dyet is a little meale and water, and not sufficient of that. Though there be fish in the Sea, foules in the ayre, and Beasts in the woods, their bounds are so large, they so wilde, and we so weake and ignorant, we cannot much trouble them. Captaine Newport we much suspect to be the Authour of those inventions. Now that you should know, I have made you as great a discovery as he, for lesse charge then he spendeth you every meale; I have sent you this Mappe of the Bay and Rivers, with an annexed Relation of the Countries and Nations that inhabit them, as you may see at large. Also two barrels of stones, and such as I take to be good Iron ore at the least; so devided, as by their notes you may see in what places I found them. The Souldiers say many of your officers maintaine their families out of that you send us: and that Newport hath an hundred pounds a yeare for carrying newes.

For every master you have yet sent can find the way as well as he, so that an hundred pounds might be spared, which is more then we have all, that helpe to pay him wages. Cap. Ratliffe is now called Sicklemore, a poore counterfeited imposture. I have sent you him home, least the company should cut his throat. What he is, now every one can tell you: if he and Archer returne againe, they are sufficient to keepe us alwayes in factions. When you send againe I intreat you rather send but thirty Carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, fisher men, blacksmiths, masons, and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided; then a thousand of such as we have: for except wee be able both to lodge them, and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for any thing. Thus if you please to consider this account, and of the unnecessary wages to Captaine Newport, or his ships so long lingering and staying here (for notwithstanding his boasting to leave us victuals for 12 moneths, though we had 89 by this discovery lame and sicke, and but a pinte of Corne a day for a man, we were constrained to give him three hogsheads of that to victuall him homeward) or yet to send into Germany or Poleland for glasse-men & the rest, till we be able to sustaine our selves, and relieve them when they come. It were better to give five hundred pound a tun for those grosse Commodities in Denmarke, then send for them hither, till more necessary things be provided.

For in over-toyling our weake and unskilfull bodies, to satisfie this desire of present profit, we can scarce ever recover our selves from ore Supply to another. And I humbly intreat you hereafter, let us know what we should receive, and not stand to the Saylers courtesie to leave us what they please, els you may charge us with what you will, but we not you with any thing. These are the causes that have kept us in Virginia, from laying such a foundation, that ere this might have given much better content and satisfaction; but as yet you must not looke for any profitable returnes: so I humbly rest.

Signed, JOHN SMITH

John Smith's Letter to Queen Anne;

an excerpt from The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624)

To the most high and vertuous Princesse Queene Anne of Great Brittanie.

Most admired Queene,

The love I beare my God, my King and Countrie, hath so oft emboldened mee in the worst of extreme dangers, that now honestie doth constraine mee presume thus farre beyond my selfe, to present your Majestie this short discourse: if ingratitude be a deadly poyson to all honest vertues, I must bee guiltie of that crime if I should omit any meanes to bee thankfull.

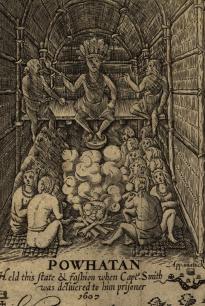

So it is,That some ten yeeres agoe being in Virginia, and taken prisoner by the power of Powhatan their chiefe King, I received from this great Salvage exceeding great courtesie, especially from his sonne Nantaquaus, the most manliest, comeliest, boldest spirit, I ever saw in a Salvage, and his sister Pocahontas, the Kings most deare and wel-beloved daughter, being but a childe of twelve or thirteene yeeres of age, whose compassionate pitifull heart, of my desperate estate, gave me much cause to respect her: I being the first Christian this proud King and his grim attendants ever saw: and thus inthralled in their barbarous power, I cannot say I felt the least occasion of want that was in the power of those my mortall foes to prevent, notwithstanding al their threats. After some six weeks fatting amongst those Salvage Courtiers, at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her owne brains to save mine; and not onely that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to James towne, where I found about eight and thirtie miserable poore and sicke creatures, to keepe possession of all those large territories of Virginia, such was the weaknesse of this poore Commonwealth, as had the Salvages not fed us, we directly had starved. And this reliefe, most gracious Queene, was commonly brought us by this Lady Pocahontas, notwithstanding all these passages when inconstant Fortune turned our peace to warre, this tender Virgin would still not spare to dare to visit us, and by her our jarres have beene oft appeased, and our wants still supplyed; were it the policie of her father thus to imploy her, or the ordinance of God thus to make her his instrument, or her extraordinarie affection to our Nation, I know not: but of this I am sure; when her father with the utmost of his policie and power, sought to surprize mee, having but eighteene with mee, the darke night could not affright her from comming through the irkesome woods, and with watered eies gave me intelligence, with her best advice to escape his furie; which had hee knowne, hee had surely slaine her. James towne with her wild traine she as freely frequented, as her fathers habitation; and during the time of two or three yeeres, she next under God, was still the instrument to preserve this Colonie from death, famine and utter confusion, which if in those times, had once beene dissolved, Virginia might have line as it was at our first arrivall to this day.

Since then, this businesse having beene turned and varied by many accidents from that I left it at: it is most certaine, after a long and troublesome warre after my departure, betwixt her father and our Colonie, all which time shee was not heard of, about two yeeres after shee her selfe was taken prisoner, being so detained neere two yeeres longer, the Colonie by that meanes was relieved, peace concluded, and at last rejecting her barbarous condition, was maried to an English Gentleman, with whom at this present she is in England; the first Christian ever of that Nation, the first Virginian ever spake English, or had a childe in mariage by an Englishman, a matter surely, if my meaning bee truly considered and well understood, worthy a Princes understanding.

Thus most gracious Lady, I have related to your Majestie, what at your best leasure our approved Histories will account you at large, and done in the time of your Majesties life, and however this might bee presented you from a more worthy pen, it cannot from a more honest heart, as yet I never begged any thing of the state, or any, and it is my want of abilitie and her exceeding desert, your birth, meanes and authoritie, hir birth, vertue, want and simplicitie, doth make mee thus bold, humbly to beseech your Majestie to take this knowledge of her, though it be from one so unworthy to be the reporter, as my selfe, her husbands estate not being able to make her fit to attend your Majestie: the most and least I can doe, is to tell you this, because none so oft hath tried it as my selfe, and the rather being of so great a spirit, how ever her stature: if she should not be well received, seeing this Kingdome may rightly have a Kingdome by her meanes; her present love to us and Christianitie, might turne to such scorne and furie, as to divert all this good to the worst of evill, where finding so great a Queene should doe her some honour more than she can imagine, for being so kinde to your servants and subjects, would so ravish her with content, as endeare her dearest bloud to effect that, your Majestie and all the Kings honest subjects most earnestly desire: And so I humbly kisse your gracious hands.

Signed, JOHN SMITH

- In two or three well thought out sentences, summarize the major point of this reading.

- In a couple of sentences, what was the bias of the author? From what perspective does the author write--political, social, and economic? Why is this significant in the document you have read?

- Different from the “what is the main point” question above, list several things that you learned from this reading, things that you did not know before doing this reading.

- The purpose of this assignment is to help you be prepared to refer to historians or historically significant individuals in your AP test essays. Identify quotes from the document that you think might be useful. Try to be selective--choose those that are genuinely typical of the writer’s thinking or that highlight a major point in the writer's thinking or argument. Include page numbers so that you can find them again when we review.

A Letter from an Indentured Servant in Virginia

By Richard Frethorne

This letter written by Richard Frethorne is included in many collections of documents from the colonial era. It presents a very negative picture of the life of an indentured servant, and it is likely that many indentured servants suffered in similar circumstances. Because indentured servants were likely to be poor and illiterate, however, few such records survive. We cannot assume, therefore, that this example is representative of the experience of every indentured servant, or even most of them. During the colonial era there must have been thousands of such servants, and a number of them must have not only survived, but become independent and prosperous on their own, though we have no figures to reflect that. What this document does reflects is the plight of poor people, not only in the American colonies, but in the mother country as well; for what but the direst of conditions could move a father and mother to sell a child into servitude?Loving and kind father and mother,